Millions of Americans are asking the wrong questions when it comes to their retirement plans. It's not "how much should I invest now?" or "is the market safe?" You should invest as much as you can in every kind of market.

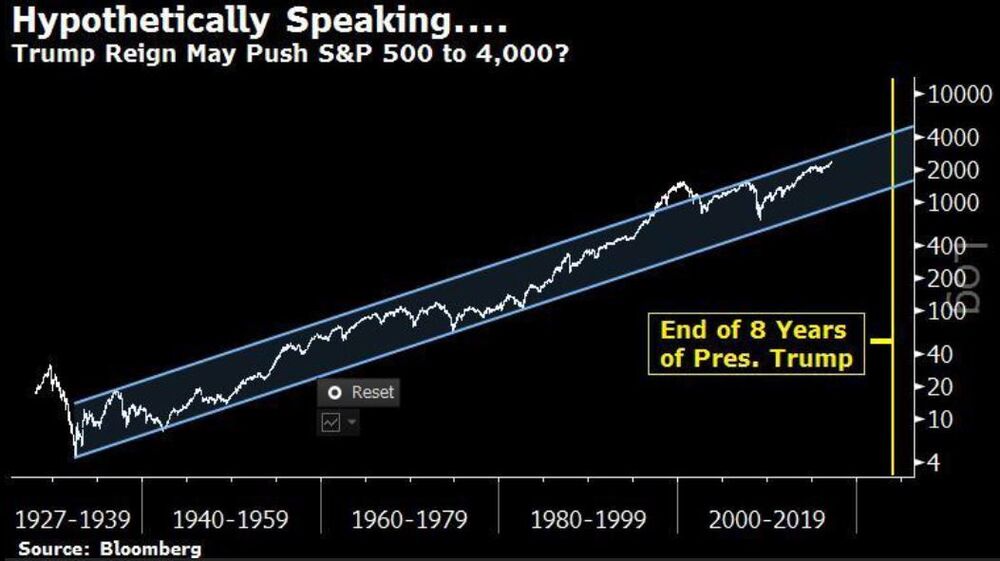

So forget about the question of whether the "Trump rally" is over, or taking a pause. If that's your concern, you're focused on the wrong thing.

Despite this reality, far too many investors are trying to find the right fund manager who can somehow predict and navigate the rocky seas the market will toss up. In rare cases, some managers get lucky and get in and out at the right time. But most don't have this ability.

Most of us want to believe that professional money managers know just when to get in and out of stocks. We put a lot of faith in them -- and mis-spend some $2 trillion in fees hoping that they'll be right and protect our money.

Shutterstock

A recent study by Jeff Ptak at Morningstar shows the folly of active management for most investors.

Ptak looked a the relationship between what actively managed funds return to the fees they charge for management. In most cases, expenses will cancel out most significant gains.

"Fees haven't fallen that steeply, and, as a result more than two-thirds of U.S. stock funds levy annual expenses that would wipe out their estimated future pre-fee excess returns."

What this means is that active managers who time the market aren't likely to outperform passive baskets of stocks. When you subtract their fees, you're not coming out ahead.

Fees take an even bigger bite when overall market returns are lower. If stocks return less than double digits, you're going to feel the pain even more.

Ptak is blunt in his conclusion: "Many active stock funds are too expensive to succeed. The exceptions are small-cap funds, where it appears fees are still below estimated pre-fee excess returns."

What can you do to avoid the meltdown of overpriced, actively managed funds? It's a pretty simple process.

1) Find the lowest-cost index funds to cover U.S. and global stocks and bonds. Expense ratios shouldn't be more than 0.20% annually (as opposed to 1% or more for active funds).

2) If you still want active funds in your portfolio, they should be highly-rated managers who invest in smaller companies.

3) Make sure that the "active" part of your portfolio is no more than 30% of your total holdings. While this is an arbitrary percentage, it will provide some buffer against market timing decisions.

You should also avoid the error of picking funds based on their past performance, which can never be guaranteed. So, instead of asking how they performed, you should ask "how many securities can they hold for the lowest-possible cost."

John F. Wasik is the author of "Lightning Strikes," "The Debt-Free Degree," "Keynes's Way to Wealth"and 13 other books on innovation, money and life. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook.