‘The Godfather’ Insight on What’s Driving Markets

It’s hard to read the events of the last few months any other way — it was the oil price all along.

Photographer: CBS Photo Archive/Getty

To get John Authers’ newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here.

Oil on Troubled Water

“The Godfather” has a quote for everything. Maybe, just maybe, it was Putin all along. Or perhaps its was Nikolai Kondratiev.

Just as Vito Corleone realized too late which rival don was pulling the strings against him, it looks ever more as though the oil price has been driving markets all along. It shouldn’t be this way. The global economy is far less oil-intense than it was in the 1970s, meaning that fuel accounts for a smaller percentage of gross domestic product. An information and services-based economy shouldn’t be so dependent on burning fossil fuels. But once the oil price rises above a certain level, investors behave as though it is. And it’s hard to read the events of the last few months any other way.

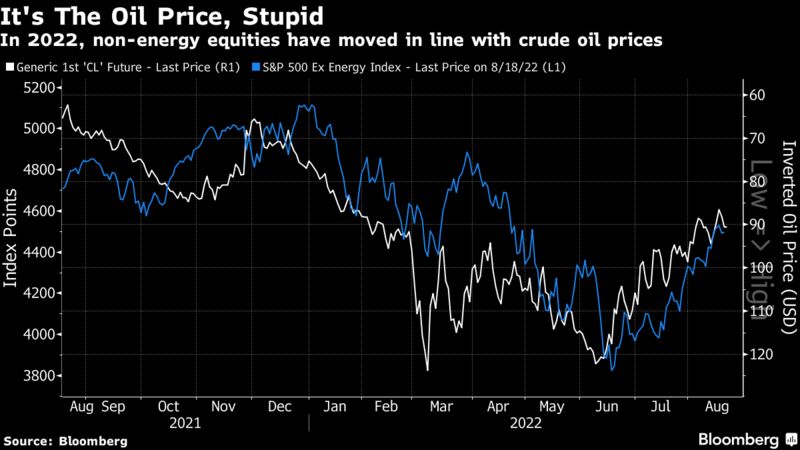

This is how the S&P 500 excluding energy has performed over the last 12 months, compared to the oil price:

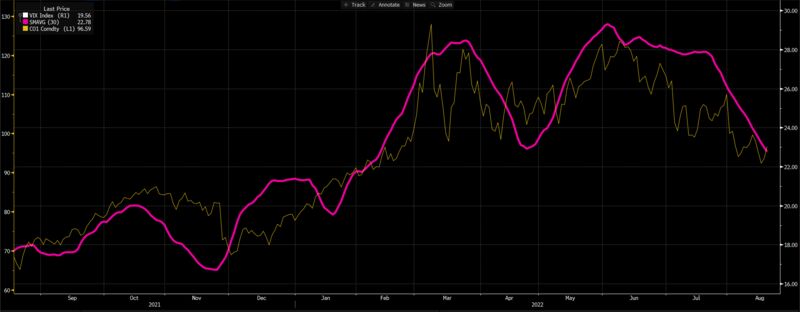

The peak and subsequent steady decline in the oil price appears to have been the critical development in turning the market. Looking instead at equity volatility, this screenshot shows the VIX 10-day moving average, in pink, against the yellow Brent crude price. Volatility has twice subsided once oil appears to have declined:

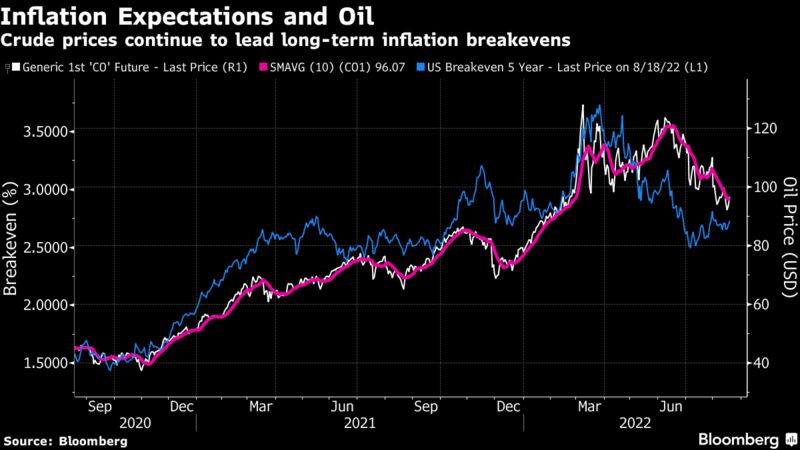

On inflation, the critical issue of the time, breakevens peaked with the first spike in the oil price after the Ukraine invasion, and started a steady decline after oil put in a further decline in mid-June. Current oil prices should have no impact on likely inflation over the next five years, but it evidently doesn’t work that way in markets:

In currency markets, oil’s impact has been strange. For many years, the dollar and the oil price had an inverse relationship — a rising oil price would mean a falling dollar compared to the euro. Thanks to the way the high oil prices now do far more economic damage in Europe than in the US, that relationship has turned on its head; rising oil has meant a weakening euro:

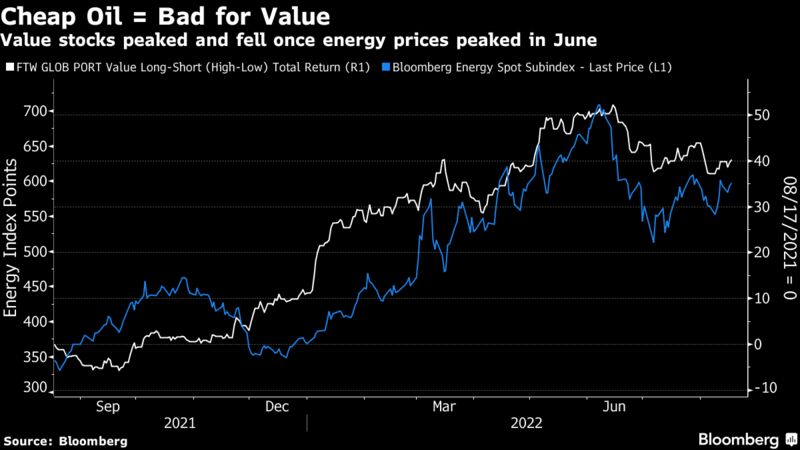

Beyond that, the June peak in the oil price also seems to have driven the decline of value compared to growth. This chart shows Bloomberg’s global measure of the performance of a value portfolio that is long the cheapest quintile of stocks and short the most expensive, again compared with the energy index:

So the decline in the oil price, combined perhaps with the steady retreat of the conflict in Ukraine from the headlines, overlapped with a big shift in market sentiment, both in areas where it would logically have an impact, and in areas where it should be irrelevant. At the margin, more controlled oil prices should mean less inflationary pressure, and a better chance that the Federal Reserve will ease interest rates (even though monetary policy has minimal impact on the energy market).

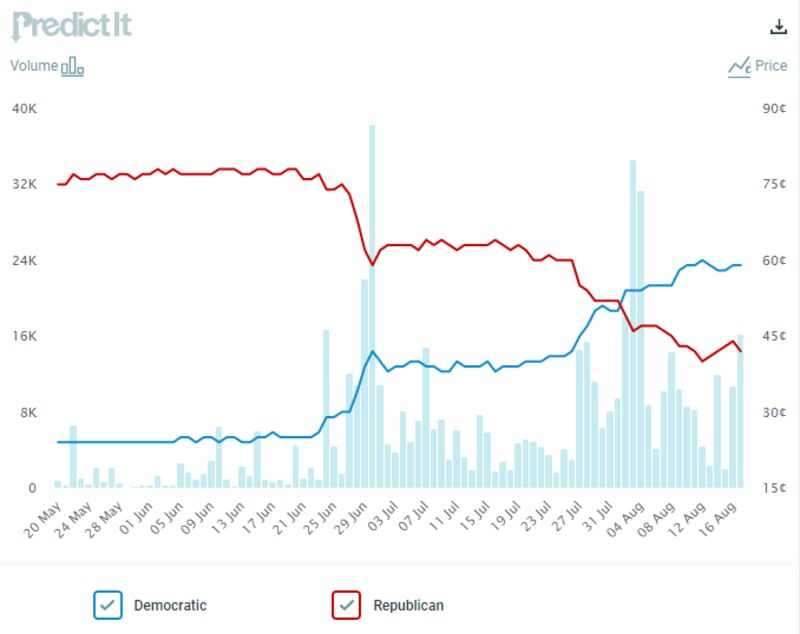

Consumer sentiment has also lifted since June, while the fortunes of the Democrats have improved, again very much in line with gas prices. This is the PredictIt prediction market’s estimate of the odds that the Democrats maintain control of the Senate in November’s election. Viewed as a very long shot in midsummer, their chances are seen to have risen steadily since the oil price peaked. The Democrats are now seen as having a 60% chance of victory (although a Republican House is still seen as overwhelmingly likely):

So, cheaper oil has made everyone much happier, which is not surprising. Is it reasonable to expect the oil price to stay under control like this? Perhaps not. Francisco Blanch, Bank of America Corp.’s head of global commodities and derivatives research, said on Bloomberg TV:

“We still have China in lockdown, we have large parts of Asia also in partial lockdown. When it comes to international travel, I think that’s going to open up in the next six to 12 months. We are down 25% on jet fuel demand globally from pre-Covid levels. We could see a pickup of half a million barrels a day, maybe more, just on that front alone... I think coming into the winter, you're going to have jet fuel demand, you're going to have demand from Europe because of the record high natural gas prices you have there. And also remember we still have a very tight global refinancing system for a variety of reasons so all of that I think is going to drag us back higher.”

All of these are reasons to expect the oil price to rebound, which is why Blanch is “definitely constructive” on Brent Crude. Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at Invesco, takes a similar line:

“I would expect oil prices to move in a range. Yes, they've come down. Some of it has been a bit artificial because we've released so much from our strategic reserves. So, I don't expect that trend to continue (the downward trend). Some of it also, I should say, has been driven by weakness in China. So, the trend could continue if we see continued weakness in China, although I continue to be more optimistic around the Chinese economy. So I think it’s much more likely to anticipate oil staying at a range. And I think that that’s comfortable. I think that that the US economy can tolerate that. I think the stock market can tolerate it because the Fed understands that it can’t impact commodity prices. It can only impact demand. And so if it’s seeing an increase in inflation coming from energy, I think it’s much less likely to act than it will in an increase in prices coming from aggregate demand going up.”

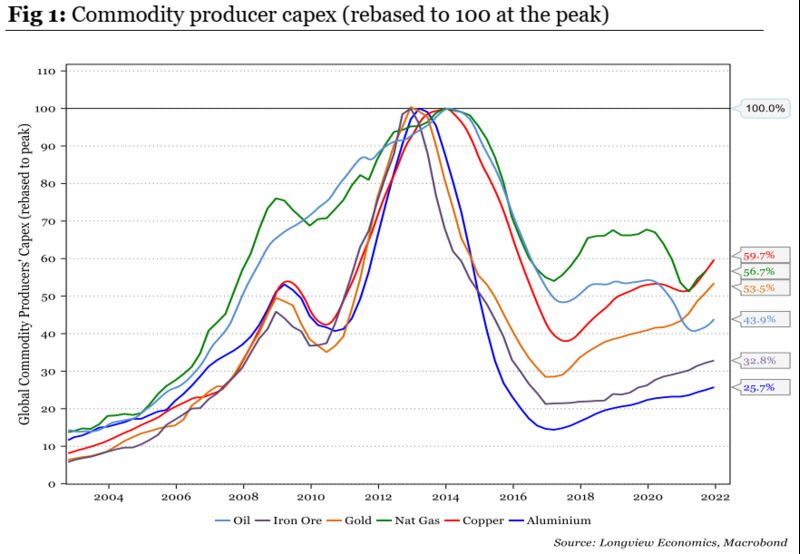

Beyond demand, there is also the issue of supply. Over time, commodity prices have tended to move in long cycles of more than a decade, with periods of rising prices punctuated by long periods when materials fall or go nowhere. It’s a phenomenon known as the Kondratiev Wave after the Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratiev, who was executed by Stalin.

In theory, the cycle is driven in large part by the inelasticity of supply. If you want to drill for more oil, or mine more metals, you need to make investments a long way in advance. What tends to happen is that capital expenditures peak at the top of the market, creating a glut of supply that forces prices down. The falling prices make producers reluctant to invest again, leading to a fall in capital expenditures, which means that they are unable to raise supply promptly the next time demand picks up. Capital expenditures for all the main commodities have barely increased over the last five years, as this chart from Longview Economics shows. And that in turn implies that the world is still on track for another classic upward commodity wave:

If commodity prices turn upward once more, investors might find the opportunity to put money into commodities to be an offer they can’t refuse. And more broadly, all investors should be aware that much of the rally in risk assets in the last two months has been predicated on a fall in the oil price. It would be a shame if it were to rise again.

Dire Straits

Here’s a hypothesis. Let’s call it the Dire Straits Conjecture. It’s never good when a narrow waterway is in the news. The recent interest in the Taiwan Strait has been terrifying — please may it soon diminish. It’s also positive that the Sea of Azov has left the headlines, and it’s very good to know that the Suez Canal is no longer blocked by a ship. Back in 1990, the world appeared to revolve around the Straits of Hormuz during the Gulf Crisis, and the Straits of Tiran signaled the end of British and French pretentions to superpower status during the Suez Crisis of 1956.

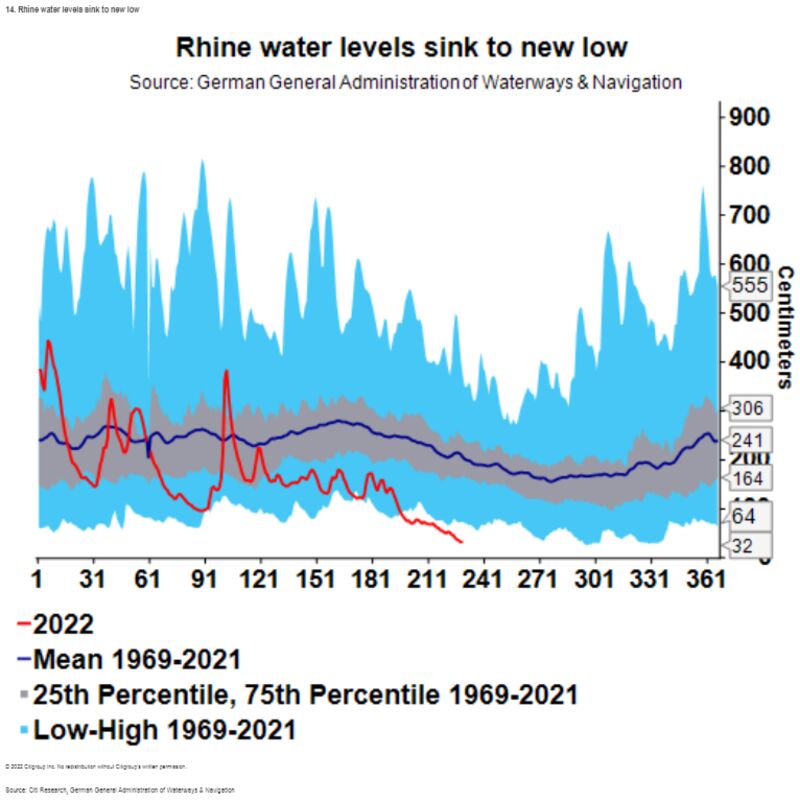

So it’s concerning that the River Rhine is in the news. A dry summer has left parts of it no longer navigable, and intensified Europe’s acute supply bottlenecks. This is from Bloomberg News’ coverage:

The level is not the actual depth of the water, which can be several feet deeper, but rather a measure for navigability. At 40 centimeters or below, many barges find it uneconomic to transit that stretch of the waterway.

To be sure, the crisis is far from over, with at least some vessels having to restrict loads if passing through the chokepoint. The low water, the result of hot and dry weather, is exacerbating a historic energy-supply crunch that is fanning inflation across the European Union and threatening to tip some of the region’s largest economies into recession.

The issue is now so consequential that it is showing up in investment bank research. This is from Citigroup:

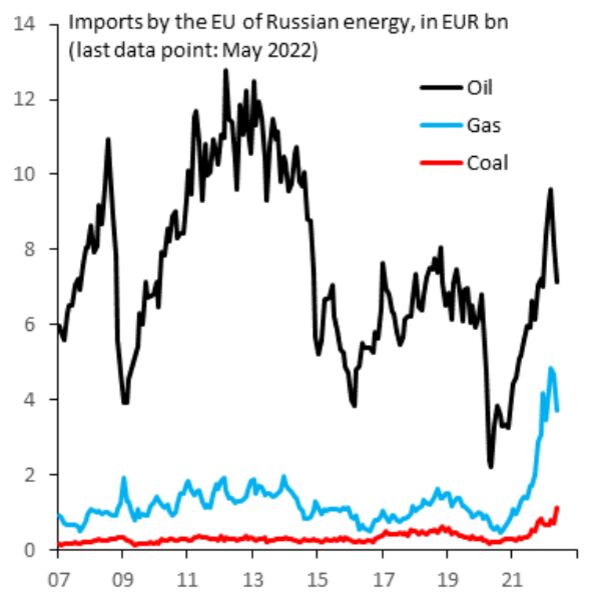

Also, lack of water in rivers is affecting France’s nuclear power output, so climate change is making itself felt very directly. This exacerbates the deeper issue, which is the EU’s response to the conflict in Ukraine. Until now, there have been sufficient energy carve-outs to the sanctions on Russian energy to leave the continent in the worst of all worlds, where consumers still face the risk of severe shortages this winter, they’re paying far more for energy than usual, and Russia’s war effort is getting funded more than adequately. The following deeply depressing chart is from the Institute of International Finance:

This then was a particularly bad time for the Rhine to run dry. Desperate attempts to alleviate the coming problems with natural gas will lead to artificial constraints on the supply of other basic materials, as BofA’s Blanch explains:

“Europe faces an obviously very complicated situation. If you look at European natural gas, 40% comes from Russia or used to come from Russia. And you’ve lost right around 10% of the entire energy supply of Europe with Russia curtailing that gas. Other things being equal, that would mean a 10% GDP contraction. And what’s happening right now essentially is Europe is trying to price itself back into the global economy so to speak by attracting liquid gas from Japan, China, bringing it into the European continent. But also importantly, we are seeing the shutdown of zinc smelters, aluminum smelters, steel plants and fertilizer capacity, so that’s all imported again. So essentially, all European energy prices are rising above global prices, but importantly a lot of the domestic-produced energy-intensive commodities like steel and what have you are also being displaced out. And that’s what Europe is doing to avoid a very very steep recession and probably end up with just a mild one.”

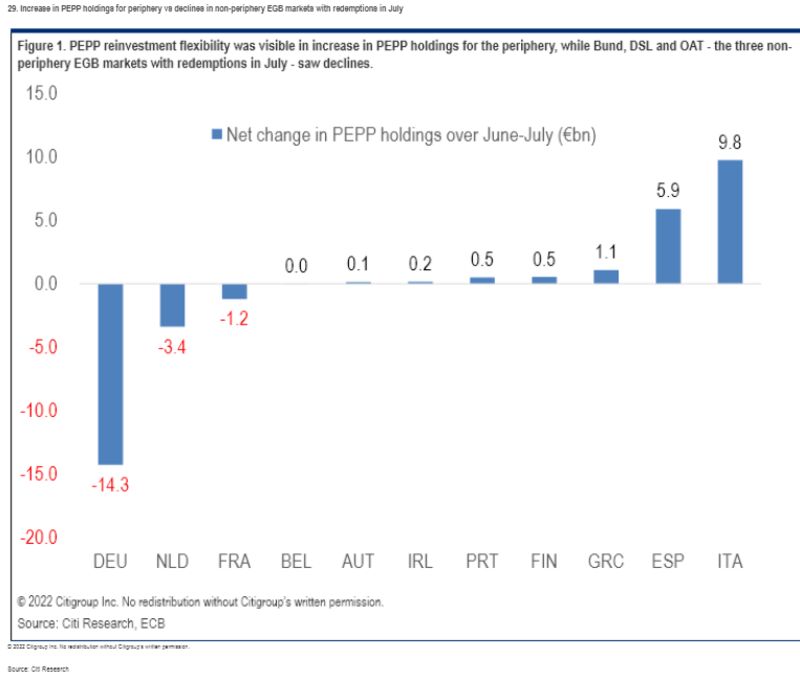

On top of all this, the attempts to keep the European peripheral countries solvent, even as the European Central Bank attempts to fight inflation by raising interest rates, looks as though it will create ever more political and economic pain. The initial sticking plaster was to use money from the PEPP (pandemic emergency purchase program) to help stop the bond yields of countries like Italy ballooning to extremes. That is translating into a direct transfer of resources. This chart from Citi shows which countries’ bonds were bought, and which were allowed to mature, during July:

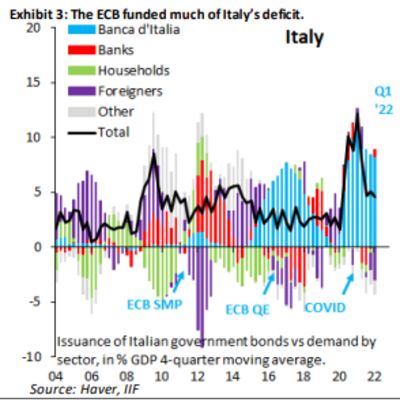

This is nothing new. As the IIF demonstrates, the ECB — acting through Italy’s central bank — has been keeping Italy afloat for years:

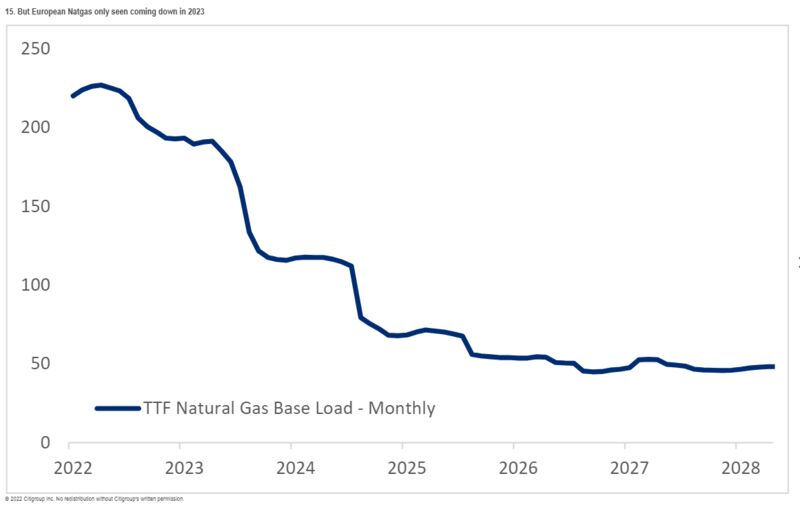

To the tensions already created by the divisions in the eurozone can be added the likely increase in natural gas prices. Futures markets suggest that they will begin to come down, but not until next year. That means the continent has a particularly bleak winter in prospect. This chart from Citi shows futures pricing for natural gas as supplied via the Netherlands:

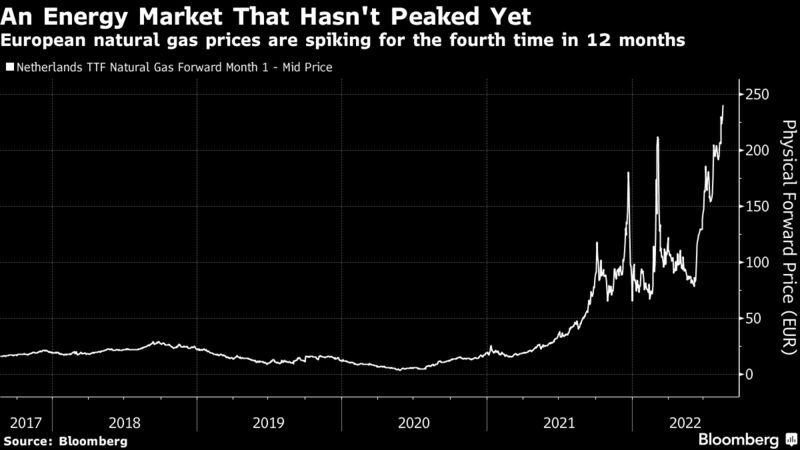

For context, this is how prices have moved over the last five years. The market is positioned for far higher gas prices than the continent has experienced before and will last for a number of years:

There is no painless way out of this. Blanch again:

“Europe is going to have to curb consumption by definition. It’s happening already with curtailments of energy supply to industry but also curtailments of temperatures at home during the summer and during the winter as well. We are going to see forced reductions, potentially rolling brownouts in some parts of Europe. This is what it looks like. And it’s almost like the developed markets are becoming like the emerging markets in a weird kind of way.”

When advanced economies need to start worrying about the depths of their rivers, and the possibility of rationing power to get through winter, it does indeed begin to sound like an emerging-market crisis, heading for Western Europe. The water level in the Rhine is expected to surge to more navigable levels next week. At some point, the river does reach the sea.

—Assistance by Isabelle Lee

Bear Market Rally, Schmear Market Rally

There’s been no shortage of debate on whether US equities are seeing a bear market bounce or a new bull market. That’s critical to help investors time the market. But fresh data reveal it might not matter that much, because it could just be better to be late than early.

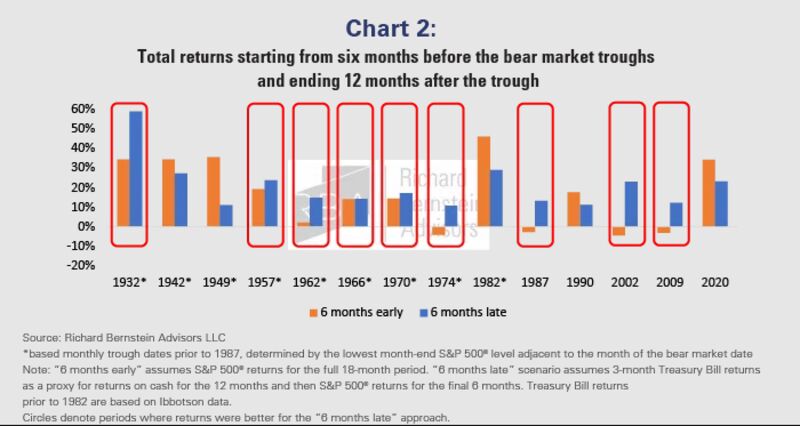

Richard Bernstein Advisors LLC analyzed the returns of a hypothetical investor around major market bottoms. The returns for entering 100% into stocks “early,” meaning six months prior to a market bottom, were compared with holding nothing but cash until six months after the market bottom and then shifting to 100% stocks “late.”

The findings are fascinating. In seven of the last 10 bear markets, the answer is clear as shown by the orange bars in the following chart:

“Not only does this tend to improve returns while drastically reducing downside potential, but this approach also gives one more time to assess incoming fundamental data,” Dan Suzuki, the firm’s deputy chief investment officer, wrote Tuesday. “Because if it’s not based on fundamentals, it’s just guessing.”

It’s not a foolproof strategy, though. In the past 70 years, there have been a handful of instances — 1982, 1990 and 2020 — where it was more profitable to be “early.” But in each of those, the Fed had already been cutting interest rates. And as the central bank launches its tightest monetary policy campaign in decades to cool inflation, albeit less aggressively than feared following its ambiguously dovish FOMC meeting, Suzuki noted it may be premature to significantly increase one’s equity exposure today.

—Isabelle Lee

Survival Tips

Should you wish to catch up on podcasts, particularly on economic themes, then my former colleague Cardiff Garcia, who now hosts The New Bazaar, has this handy and exhaustive list of the audio you should try listening to. If you need some reading instead, this is the long list of the books in contention for this year’s Financial Times/McKinsey Business Book of the Year award. There are plenty of very interesting-sounding titles in there.