Cryptocurrencies: A Necessary Scam?

Yes, Web3 is a bunch of bullshit. The problem is, compared to what?

| 66 | 178 |

Welcome to BIG, a newsletter about the politics of monopoly. If you’d like to sign up, you can do so here. Or just read on…

For a few years, I’ve been thinking about why social movements like crypto and bitcoin have so much momentum. I often get emails from proponents of crypto as an anti-monopoly tool, and a lot of smart people that I respect believe that it is based on a groundbreaking technology that will sweep the world. I don’t see it that way. I think it’s a social movement based on a dangerous get-rich-quick scam. But there’s a tremendous amount of goodwill involved, and as with GameStop, the underlying driver of the energy in this movement is mass and legitimate disillusionment with liberal institutions who have failed to deliver.

This weekend, I held a forum for paid subscribers on whether crypto is a useful anti-monopoly tool, and the debate got heated. I learned a lot, and after reading the comments, I decided to write an essay, because it seems like there’s a lot of confusion about what crypto is and what it’s for. Today, for instance, there’s a hearing in the House Financial Services Committee on the crypto, with lots of talk about innovation along with warnings about risks and regulation. While useful, such traditional financial reform chatter obscures the far more interesting political debate that crypto has brought to the surface of our society about finance, monopoly, and the state itself.

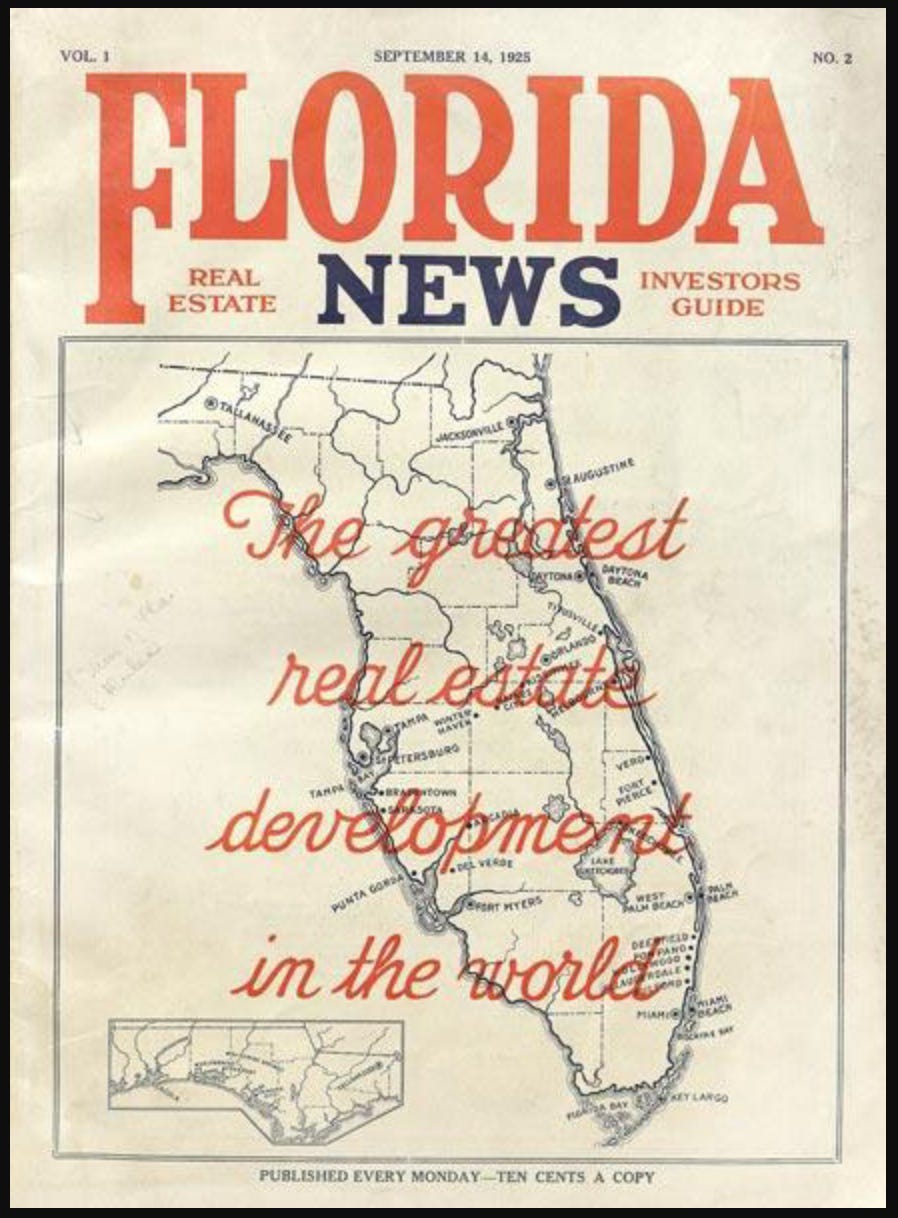

To explain what is going on, I think it helps to start with a historical analogy, the state that always seems to be a critical ingredient of every financial crisis. Florida. In particular, Florida in the 1920s.

In the early 1920s, just after a horrific war and decades of reform that ended in cynicism, a wave of speculation occurred around land in Florida. Thousands of disillusioned Americans in the Northeast sought to get rich quick, like the ‘mushroom millionaires’ who had profited in the Great War that killed so many. These speculators used financial instruments and easy money, the equivalent of deregulation, to gamble massively across the economy. The mania became so insane that there was speculation over land lots in the city of Nettie, Florida, a city which later turned out not to exist. Eventually, the bubble popped. First, multiple hurricanes hit the state. The stock market did the rest by crashing in 1929. The result was tears, losses and decades of litigation.

And with that, let’s talk crypto. Cryptocurrencies are a social movement based on the belief that markings in a ledger on the internet have intrinsic value. The organizers of these ledgers call these markings Bitcoin, or Dogecoin, or offer other names based on the specific ledger. That’s really all a cryptocurrency is. There’s no magic. It’s not money, though it has money-like properties. It’s not anything except a set of markings. Sure, the technology behind the ledgers and how to create more of these markings is kind of neat. But crypto is a movement based on energetic storytellers who spin fables about the utopian future to come. In a lot of ways, cryptocurrencies are like Florida land that no one ever intends to use. It has value in the moment it is traded, but only because there’s a collective belief that it has some intrinsic worth. (There is a wide variety of ‘tools’ in the crypto world, like NFTs, smart contracts, and global computing systems, but they don’t work, and none of them have any use cases except speculation and money-laundering, and even in their idealized form they have no use cases aside from doing stuff you can already do far more easily through existing technology, with a different permissioning model.)

That said, the crypto narrative is one that anti-monopolists in general find deeply compelling, since both the anti-monopoly movement and the cryptocurrency movement emerged out of the financial crisis. Elizabeth Warren became a Senator out of the crisis, and eventually pivoted to making the first call to break up big tech. Bitcoin was created on January 3, 2009, a few weeks before Barack Obama was inaugurated. Inscribed in the code of Bitcoin is the following phrase, “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.” Both crypto and the anti-monopoly movement are reactions to the destruction wrought by neoliberalism.

Both financial crisis reformers and Bitcoin proponents believe that the existing financial order is a collusive arrangement between large banks who are supported by government power. Money laundering, tax evasion, criminal activity, and fraud are fine as long as you are an insider in this system, and the Federal Reserve and various other government institutions will not only not stop corrupt insiders, but will subsidize and bail them out if necessary. Meanwhile, the rest of us have to live with foreclosures, high interest rates on credit cards, and high fees for middlemen in every aspect of the economy.

Indeed, it’s hard to see how our social contract is legitimate or fair. No one went to jail for the financial crisis, and the ongoing parade of scandals is nonstop. Just to take a random story that came out last week, several groups published a finding that the $11 trillion private investment industry is a haven for money laundering. We all know there will be no state reaction to fix this.

So what is to be done? The traditional populist view is that we should reform our social order through politics, things like mass education, elections, and civic engagement. That’s how Elizabeth Warren sees the world. She wants to strengthen the state so it can restore the social order, one that will tolerate less cheating and will involve the rule of law applied to the powerful.

The crypto response is different. The crypto response is to reject the social contract itself as irredeemably corrupt. Their goal is put pressure on the state itself by creating a money-like instrument outside of the public rule-setting capacity of the government. This is framed in the name of consumer choice, as in the state shouldn’t be able to boss you around and tell you what you can do with your money. After all, it’s yours. And anyone who doesn’t buy into this idea is inherently defending a set of collusive bailout-friendly institutions that we sometimes call liberal democracy.

But core to having a state, even a democratic one, is the ability to ban things and use coercion to enforce such a ban. Societies and social contracts are built on cooperative mechanisms, but also barriers and enforceable rules. In this framework, the argument of crypto proponents makes no sense. It is basically, ‘You can’t tell me not to have access to a money-like mechanism, even if the point of this instrument is to defraud people or engage in ransomware attacks, and even if we know that the ultimate endpoint is a giant collapse when people trapped in a liquidity crisis find out that there is no lender of last resort for Bitcoin or any of the other cryptocurrencies. If you do, that’s tyranny.’

In other words, skeptics of cryptocurrencies generally believe that cryptocurrencies are easily manipulated mechanisms to launder money, commit fraud, evade sanctions, empower dictators, engage in heavily leveraged speculation prone to collapse, and ultimately break the state itself. The response to this concern is easy - exactly how is this accusation any different than the existing order? Surely if insiders are allowed to cheat in our regulated banking system, then why should we treat it as legitimate? Why not build our own financial channels? Yeah, maybe it’s bad, but at least we’re not Goldman Sachs or AIG.

That’s why I don’t think this movement can be dismissed as merely get rich quick mania. There’s goodwill and energy behind this movement, as well as a lot of wealthy cynics and scam artists. But the lack of legitimacy of liberal democracies is real. Increasingly, though, the arguments from cryptocurrency proponents are changing. They are saying they want to be regulated, they are not opposed to the state, they are just into technological innovation, and so forth. That’s why every witness in today’s hearing said they want regulation by the state. I don’t buy it.

We’re in new stage, where some very scary people are taking over monetary politics. If crypto boosters sought aggressive reform of the existing financial order, democratizing the Fed, clamping down on big banks, and so forth, and said that until that happens, they will pursue alternative currencies, that would be one thing. But that’s not at all how the politics of crypto works. In D.C., those who opposed the bailouts and sought to break up the banks - the reformers - are the most skeptical of cryptocurrencies. Meanwhile, the pro-crypto lobby includes men like Pat Toomey, the most pro-bailout and pro-Fed politician in D.C., and is financed by libertarian billionaire Marc Andreessen, a key force behind the rise of Facebook. Led by the leaders of Miami and New York City, a wave of mayors are actively trying to fuse cryptocurrencies to local governments, with Miami mayor Francis Suarez asserting that these are ‘natural resources’ and telling voters they may never have to pay taxes.

The amount of utopian bullshit and fake promises on a technology that doesn’t really work as anything but a speculative bubble and money laundering device should be a big red flag. Crypto is a movement based on the theory that the existing nation-state is a system rigged by billionaires, and the right response is to create a different and more corrupt order rigged by different billionaires, money launderers, and dictators. It will of course all end in tears, ironically when the Fed ends its monetary stimulus creating bubbles across the economy. That much we know. But how much ruin this movement engenders will depend on whether and how quickly we can restore the legitimacy of our existing governing systems.

Thanks for reading.

And please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or comments by clicking on the title of this newsletter. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation and democracy. And consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member.

cheers,

Matt Stoller