Warren Buffett's Cash Problem

Summary

In this article I decided to dig into the question regarding Berkshire Hathaway's cash and what it means for the firm.

As opposed to sticking solely with the $20 billion benchmark so often thrown out there, I looked at how cash stacks up against other metrics.

For the most part, even by historically-elevated standards, cash still looks to be too high and this likely means some sort of action will take place in the near future.

Most likely this will result in an acquisition but while it's impossible to know which company it might be, I have my own pick that I'd love to see completed.

As opposed to sticking solely with the $20 billion benchmark so often thrown out there, I looked at how cash stacks up against other metrics.

For the most part, even by historically-elevated standards, cash still looks to be too high and this likely means some sort of action will take place in the near future.

Most likely this will result in an acquisition but while it's impossible to know which company it might be, I have my own pick that I'd love to see completed.

One company that is hard for investors to not keep a close eye on is Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A) (NYSE:BRK.B).

Not only is the firm the financial/investment embodiment of Warren

Buffett's value investing philosophy, it's also one of the largest

publicly traded companies on the face of the planet with a market cap,

as of the time of this writing, of $408.74 billion. By every measure,

Berkshire is a behemoth.

I should say that, given the company's strong financial performance since Buffett took over decades ago and the philosophy that guides it, I believe the business may be one of the best long-term prospects for investors out there (for those looking for "safer" and steady returns) and if I were planning on buying any company knowing that I'd be heading into a 20-year coma the next day, Berkshire would probably take a very close second place for me right behind The Walt Disney Company (NYSE:DIS). That said, while looking over the firm's financials again, I noticed something that warrants some discussion: Buffett's large cash position.

A look at Berkshire's cash

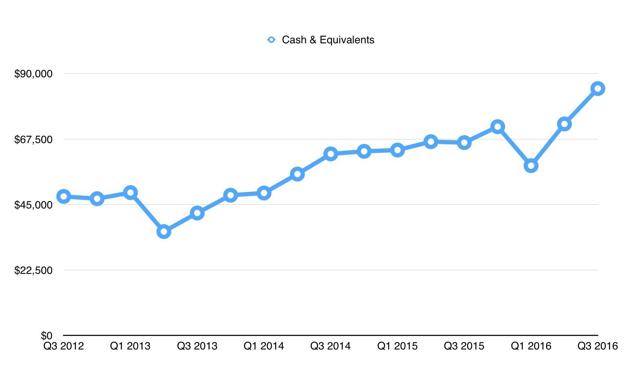

The saying that cash is king has a ring of truth to it but there are limits to how much cash a person or company should hold. You see, while cash is great to have in the event a major market downturn comes along, keeping it on your balance sheet also means that you're missing out on attractive opportunities. In the past, Buffett has said he generally likes to have around $20 billion in cash on hand but today, as you can see in the graph below, he has far more than that.

*Created by Author

The graph in question shows that, as of the end of Berkshire's third quarter, the company has cash and cash equivalents on hand totaling $84.84 billion, the largest the company has ever posted. In fact, the closest we have seen to this came in the second quarter of this year when cash came out to $72.68 billion (a difference of $12.16 billion!). However, the question becomes whether or not the cash is truly too much.

http://seekingalpha.com/article/4033082-gauging-warren-buffetts-cash-problem

You see, while Buffett aims to hold cash of around $20 billion and would like to deploy the rest in order to grow Berkshire or, when appropriate, buy back stock, we also need to keep in mind that a company's needs change. Take, for instance, a firm that doubles in size over a few years. If $20 billion was a sweet spot for said firm before it doubled, then its increased operations should mean that some amount around $40 billion is now appropriate (maybe a little less or a little more). In essence, we're dealing with a dynamic system here, not a static one where a fixed dollar amount should be the ideal in perpetuity.

*Created by Author

So, to move away from the fixed dollar amount argument that other Buffett cash articles have made, I decided to look at cash relative to the company as a whole. One such example can be seen in the graph above, which compares Berkshire's cash to its assets as a whole over the past five years (using quarterly data). What you can see here is that, in addition to cash rising as a whole since the third quarter of 2012, it has also risen as a percent of assets, climbing from its five-year average of 11.24% to 14.04%.

*Created by Author

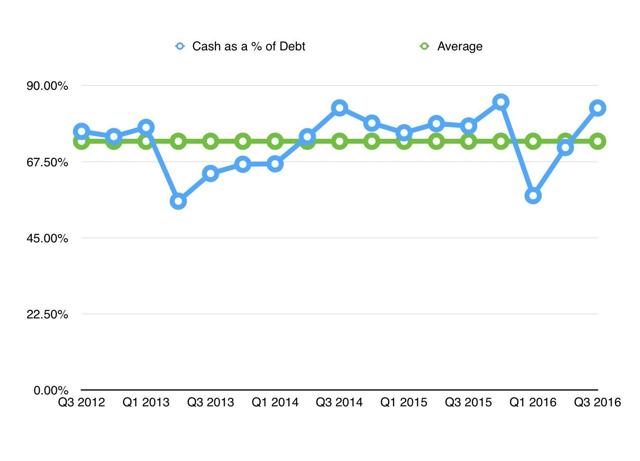

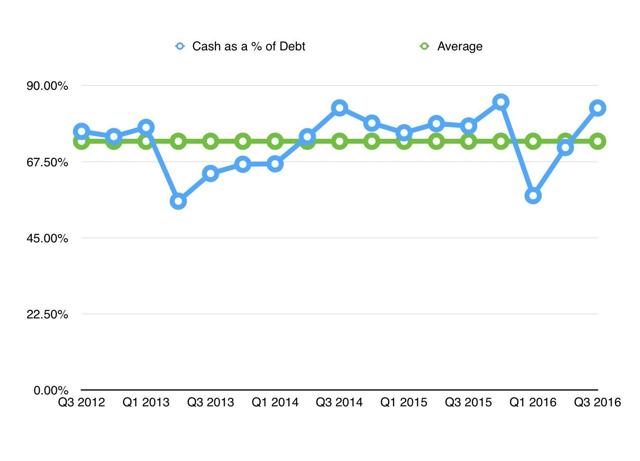

Beyond just assets, however, I decided to look into cash as a percent of debt and cash as a percent of investments, pictured above and below, respectively. The reason here is that, due to the nature of assets and the nature of companies adopting leverage, we need to be cognizant of areas where anomalies could develop. Take, for instance, a scenario where Berkshire might drastically increase its cash but it also saw a massive uptick in debt. Well, that just means the company is borrowing now for the sake of financial flexbility, which means "excess cash" is an operational and accounting convention that must be reconciled.

*Created by Author

Changes in investments could also have implications here since when investments are sold (and in Berkshire's case, a lot of its investments can be sold quickly if need be), the end result, without any offsetting scenario where cash is sent out of the company once again, is more cash. A very good example regarding Berkshire came during the second quarter. Previously, the firm held onto preferred shares of Kraft-Heinz (NASDAQ:KHC) that paid the company a 9% dividend each year. On June 7th of this year, Kraft-Heinz decided to redeem these shares, which was instrumental in reducing Berkshire's investments from $163.25 billion to $158.91 billion over the course of a quarter and transferred to Berkshire cash of $8.32 billion. This is why, in the graph above, the departure of Berkshire from close to its average cash as a percent of investments was so volatile.

What to do?

If we look at Berkshire's cash position over the past few years, we can arrive at the conclusion that not only does the firm seem to have a large amount of cash relative to the $20 billion benchmark but, even by historical norms compared to already elevated levels, its cash position is abnormally large (though by the percent of debt method, this appears to not be the case all that much). This begs the question of what, in Buffett's mind, is next.

You see, Buffett is not the kind of investor who will solve the problem the way Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) did when it decided to pay out a distribution. For better or worse (I believe better), Buffett will almost certainly never pay out any dividends to shareholders. This leaves a few different options. First, he could be saving the cash up for a rainy day, a period of time when the markets fall irrationally lower, possibly as a result of an economic downturn. Given his mindset regarding trying to time the market, namely that, "People that think they can predict the short-term movement of the stock market - or listen to other people who talk about (timing the market) - they are making a big mistake".

Share buybacks are also unlikely due to the fact that, in the past, Buffett has been vocal about when he is interested in making sizable moves. Generally speaking, this is when the company is trading around 1.20 times book value or less. Using Berkshire's third quarter book value, we're looking at a threshold of $327.14 billion so, right now, shares would need to fall quite a bit (around 20%) before that becomes reasonable.

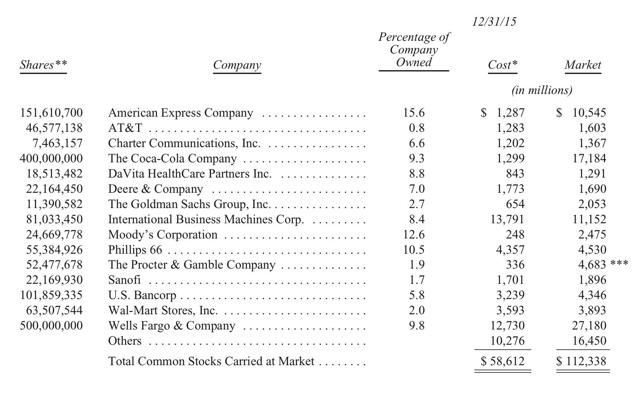

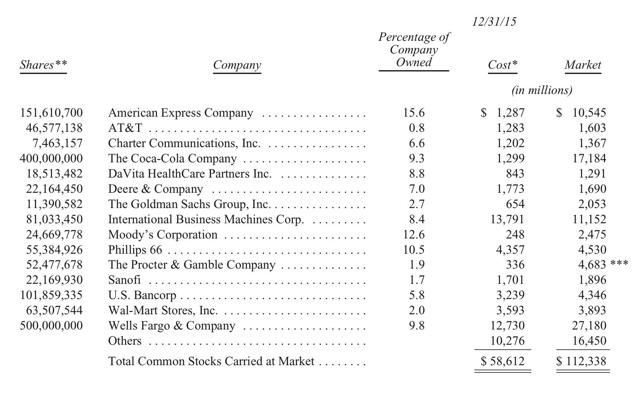

The last option we can look at would be an acquisition of some sort. Last year, the firm bought up all of Precision Castparts, its largest acquisition ever, in an all-cash deal of $32 billion and the company has made a number of other large purchases over the years, such as Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Lubrizol, so seeing something of this nature sometime soon would make sense. It's impossible to know which company it might be but I'd bet my money on a company Berkshire already owns shares in. In the image below, you can see a list of Berkshire's investments as of the end of last year and the percent of the companies the business owns as a result.

*Taken from Berkshire Hathaway

I will not pretend to guess what Buffett's next move might be (if I ever get a psychic vision like that, I'll sell it to the highest bidder) but one interesting idea that pops to my mind is a purchase of The Coca-Cola Company (NYSE:KO). While the share count of Berkshire's other holdings have changed over the past year, the firm continues to hold the same 400 million shares, currently worth $16.64 billion, that it held at the end of 2015, representing nearly 9.3% of the enterprise.

At this moment, Coca-Cola is worth $179.42 billion on the open market so it would cost Buffett $162.78 billion to buy the firm at what it's worth today (what it doesn't already own). Of course, this isn't the end price that would be paid because some premium (likely a hefty one) would need to be applied. That said, even if Buffett paid a $40 billion premium on the company using shares of Berkshire (he doesn't like doing this but given their price right now, combined with the fact that he used this method when acquiring Burlington Northern Santa Fe, it may be an option), bought Coca-Cola using Berkshire's cash plus Coca-Cola's cash (leaving the $20 billion minimum he likes to see), a deal could get done with $72.38 billion in debt which, at 5% interest (most of Berkshire's debt is below 5%), would cost $3.62 billion per year.

Ignoring the tax shield implications here, which would only benefit Berkshire, the math still works well for the company. This is due to the fact that, in the first three quarters of this year alone, Coca-Cola has generated operating cash flow of $6.72 billion. Beyond the cash flow, however, the company's simplicity, strong brand and continued growth potential make it a Buffett-esque play and a large cash cow that Buffett has owned shares in since 1988 (he acquired around 7% of the business by early 1989). It would be a great capstone to Buffett's long and successful career.

Takeaway

Right now, neither I nor anybody else knows for sure what, exactly, Buffett has in mind regarding Berkshire's cash but we can conclude three things: 1) the firm has a lot of excess cash right now, 2) Buffett's not a fan of too much cash, and 3) he likes acquiring companies and this seems to be more reasonable right now than any other alternative. All of this seems to be pointing at another major acquisition (or a series of small ones like the $634 million spread across 29 bolt-ons seen last year) but figuring out when and what is more or less impossible. Personally I would like to see Buffett take a crack at a big player like Coca-Cola or Disney but the important thing is that the catalyst is already in place for him to buy something in the near future.

I should say that, given the company's strong financial performance since Buffett took over decades ago and the philosophy that guides it, I believe the business may be one of the best long-term prospects for investors out there (for those looking for "safer" and steady returns) and if I were planning on buying any company knowing that I'd be heading into a 20-year coma the next day, Berkshire would probably take a very close second place for me right behind The Walt Disney Company (NYSE:DIS). That said, while looking over the firm's financials again, I noticed something that warrants some discussion: Buffett's large cash position.

A look at Berkshire's cash

The saying that cash is king has a ring of truth to it but there are limits to how much cash a person or company should hold. You see, while cash is great to have in the event a major market downturn comes along, keeping it on your balance sheet also means that you're missing out on attractive opportunities. In the past, Buffett has said he generally likes to have around $20 billion in cash on hand but today, as you can see in the graph below, he has far more than that.

*Created by Author

The graph in question shows that, as of the end of Berkshire's third quarter, the company has cash and cash equivalents on hand totaling $84.84 billion, the largest the company has ever posted. In fact, the closest we have seen to this came in the second quarter of this year when cash came out to $72.68 billion (a difference of $12.16 billion!). However, the question becomes whether or not the cash is truly too much.

http://seekingalpha.com/article/4033082-gauging-warren-buffetts-cash-problem

You see, while Buffett aims to hold cash of around $20 billion and would like to deploy the rest in order to grow Berkshire or, when appropriate, buy back stock, we also need to keep in mind that a company's needs change. Take, for instance, a firm that doubles in size over a few years. If $20 billion was a sweet spot for said firm before it doubled, then its increased operations should mean that some amount around $40 billion is now appropriate (maybe a little less or a little more). In essence, we're dealing with a dynamic system here, not a static one where a fixed dollar amount should be the ideal in perpetuity.

*Created by Author

So, to move away from the fixed dollar amount argument that other Buffett cash articles have made, I decided to look at cash relative to the company as a whole. One such example can be seen in the graph above, which compares Berkshire's cash to its assets as a whole over the past five years (using quarterly data). What you can see here is that, in addition to cash rising as a whole since the third quarter of 2012, it has also risen as a percent of assets, climbing from its five-year average of 11.24% to 14.04%.

*Created by Author

Beyond just assets, however, I decided to look into cash as a percent of debt and cash as a percent of investments, pictured above and below, respectively. The reason here is that, due to the nature of assets and the nature of companies adopting leverage, we need to be cognizant of areas where anomalies could develop. Take, for instance, a scenario where Berkshire might drastically increase its cash but it also saw a massive uptick in debt. Well, that just means the company is borrowing now for the sake of financial flexbility, which means "excess cash" is an operational and accounting convention that must be reconciled.

*Created by Author

Changes in investments could also have implications here since when investments are sold (and in Berkshire's case, a lot of its investments can be sold quickly if need be), the end result, without any offsetting scenario where cash is sent out of the company once again, is more cash. A very good example regarding Berkshire came during the second quarter. Previously, the firm held onto preferred shares of Kraft-Heinz (NASDAQ:KHC) that paid the company a 9% dividend each year. On June 7th of this year, Kraft-Heinz decided to redeem these shares, which was instrumental in reducing Berkshire's investments from $163.25 billion to $158.91 billion over the course of a quarter and transferred to Berkshire cash of $8.32 billion. This is why, in the graph above, the departure of Berkshire from close to its average cash as a percent of investments was so volatile.

What to do?

If we look at Berkshire's cash position over the past few years, we can arrive at the conclusion that not only does the firm seem to have a large amount of cash relative to the $20 billion benchmark but, even by historical norms compared to already elevated levels, its cash position is abnormally large (though by the percent of debt method, this appears to not be the case all that much). This begs the question of what, in Buffett's mind, is next.

You see, Buffett is not the kind of investor who will solve the problem the way Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) did when it decided to pay out a distribution. For better or worse (I believe better), Buffett will almost certainly never pay out any dividends to shareholders. This leaves a few different options. First, he could be saving the cash up for a rainy day, a period of time when the markets fall irrationally lower, possibly as a result of an economic downturn. Given his mindset regarding trying to time the market, namely that, "People that think they can predict the short-term movement of the stock market - or listen to other people who talk about (timing the market) - they are making a big mistake".

Share buybacks are also unlikely due to the fact that, in the past, Buffett has been vocal about when he is interested in making sizable moves. Generally speaking, this is when the company is trading around 1.20 times book value or less. Using Berkshire's third quarter book value, we're looking at a threshold of $327.14 billion so, right now, shares would need to fall quite a bit (around 20%) before that becomes reasonable.

The last option we can look at would be an acquisition of some sort. Last year, the firm bought up all of Precision Castparts, its largest acquisition ever, in an all-cash deal of $32 billion and the company has made a number of other large purchases over the years, such as Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Lubrizol, so seeing something of this nature sometime soon would make sense. It's impossible to know which company it might be but I'd bet my money on a company Berkshire already owns shares in. In the image below, you can see a list of Berkshire's investments as of the end of last year and the percent of the companies the business owns as a result.

*Taken from Berkshire Hathaway

I will not pretend to guess what Buffett's next move might be (if I ever get a psychic vision like that, I'll sell it to the highest bidder) but one interesting idea that pops to my mind is a purchase of The Coca-Cola Company (NYSE:KO). While the share count of Berkshire's other holdings have changed over the past year, the firm continues to hold the same 400 million shares, currently worth $16.64 billion, that it held at the end of 2015, representing nearly 9.3% of the enterprise.

At this moment, Coca-Cola is worth $179.42 billion on the open market so it would cost Buffett $162.78 billion to buy the firm at what it's worth today (what it doesn't already own). Of course, this isn't the end price that would be paid because some premium (likely a hefty one) would need to be applied. That said, even if Buffett paid a $40 billion premium on the company using shares of Berkshire (he doesn't like doing this but given their price right now, combined with the fact that he used this method when acquiring Burlington Northern Santa Fe, it may be an option), bought Coca-Cola using Berkshire's cash plus Coca-Cola's cash (leaving the $20 billion minimum he likes to see), a deal could get done with $72.38 billion in debt which, at 5% interest (most of Berkshire's debt is below 5%), would cost $3.62 billion per year.

Ignoring the tax shield implications here, which would only benefit Berkshire, the math still works well for the company. This is due to the fact that, in the first three quarters of this year alone, Coca-Cola has generated operating cash flow of $6.72 billion. Beyond the cash flow, however, the company's simplicity, strong brand and continued growth potential make it a Buffett-esque play and a large cash cow that Buffett has owned shares in since 1988 (he acquired around 7% of the business by early 1989). It would be a great capstone to Buffett's long and successful career.

Takeaway

Right now, neither I nor anybody else knows for sure what, exactly, Buffett has in mind regarding Berkshire's cash but we can conclude three things: 1) the firm has a lot of excess cash right now, 2) Buffett's not a fan of too much cash, and 3) he likes acquiring companies and this seems to be more reasonable right now than any other alternative. All of this seems to be pointing at another major acquisition (or a series of small ones like the $634 million spread across 29 bolt-ons seen last year) but figuring out when and what is more or less impossible. Personally I would like to see Buffett take a crack at a big player like Coca-Cola or Disney but the important thing is that the catalyst is already in place for him to buy something in the near future.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours.

I wrote this

article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving

compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business

relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.